Rise and shine, kids. Today we’re looking at the Chernobyl Nuclear Accident in 1986.

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP)

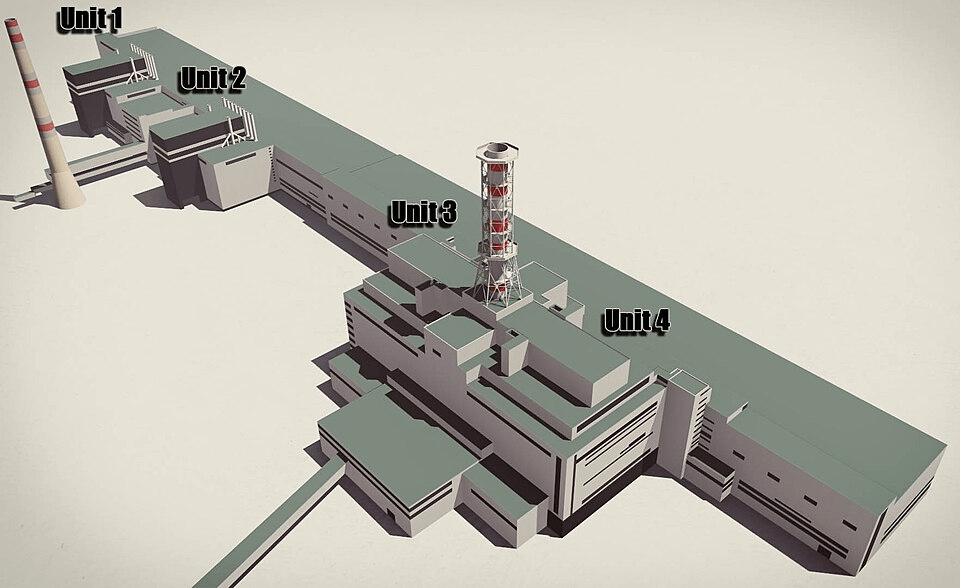

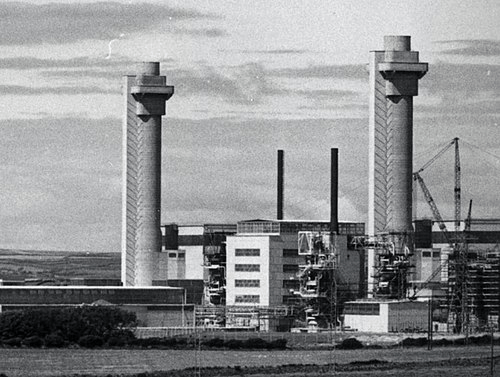

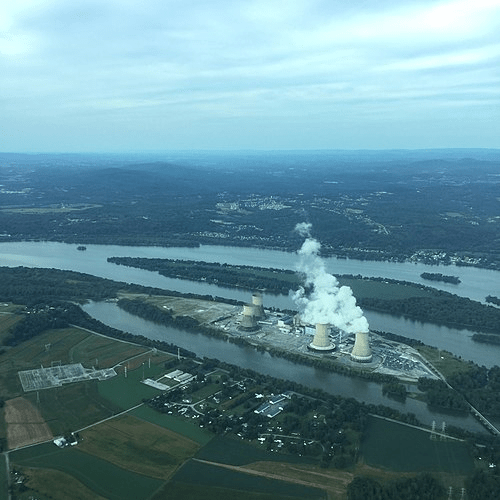

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (originally Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant of V. I. Lenin) was a nuclear power plant currently undergoing a process of decommissioning. This reactor is located near the city of Pripyat in northern Ukraine, 100 km (62 mi) north of Kyiv. The plant entered commission in 1977-8, with unit 1. Before the infamous disaster, the plant had 4 units in total, all equipped with the famous RBMK-1000 reactor (however, the original plan was to equip the plant with 12 of such reactors).

Construction began in 1972, with unit 1 being completed in 1977, followed by unit 2 in 1978, unit 3 in 1981, and unit 4 in 1983. During the time of the disaster, reactor number 5 and 6 were in construction.

Even after the disaster in 1986, the rest of the reactors ran to provide power, especially after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when Ukraine stopped getting their power from the rest of the Union. Unit 2 was permanently shut down in 1991 after a turbine fire, and unit 1 was shut down in 1996 and unit 3 in 2000 after an agreement with the European Union.

The Disaster

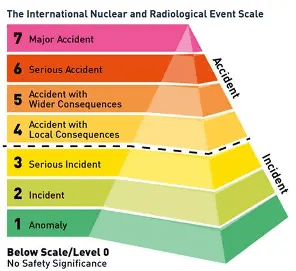

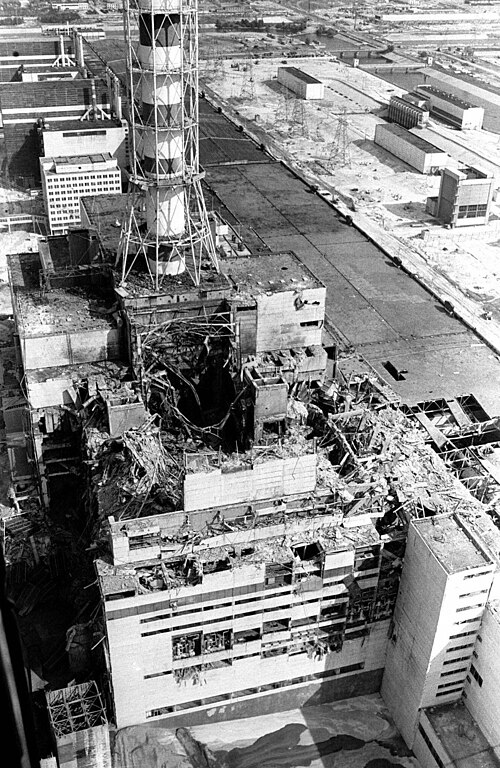

On 26 April 1986, unit 4 of the ChNPP, located near Pripyat, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union exploded. It remains one of only 2 nuclear accidents rated 7 of the international nuclear event scale.

The disaster happened while operators were conducting a safety test of simulating cooling the reactor during an accident in blackout conditions. The cause of the accident is partially due to operator errors but mainly falls on the reactor’s design. Shutting down the reactor in certain conditions, like the ones during the accident, resulted in a power surge, resulting in a steam explosion and meltdown of unit 4.

The Safety Test

The test was supposed to be conducted by the day-shift personnel of 25 April 1986. However, another power station in the region went offline, and at 14:00, Kyiv’s electrical grid controller that the safety test be postponed dealing with the power demand. The dayshift was replaced with the night shift, and at 23:04, the grid controllers gave the green light for the test. Anatoly Dyatlov was set to direct the test. The test procedure was as follows:

- The reactor thermal power was to be reduced to between 700 MW and 1,000 MW (to allow for adequate cooling, as the turbine would be spun at operating speed while disconnected from the power grid)

- The steam-turbine generator was to be run at normal operating speed

- Four out of eight main circulating pumps were to be supplied with off-site power, while the other four would be powered by the turbine

- When the correct conditions were achieved, the steam supply to the turbine generator would be closed, which would trigger an automatic reactor shutdown in ordinary conditions

- The voltage provided by the coasting turbine would be measured, along with the voltage and revolutions per minute (RPMs) of the four main circulating pumps being powered by the turbine

- When the emergency generators supplied full electrical power, the turbine generator would be allowed to continue free-wheeling down

As shown, the test requires a decrease in reactor power to around 700-1000MW thermal, and by 00:05 on the 26th of April, 720MW was reached. However, due to a byproduct in fission called Xenon-135 which absorbs neutron, the power kept decreasing. This is called ‘Reactor Poisoning’. In normal operations, this can usually be avoided, as the Xenon-135 burns off and becomes the more stable Xenon-136. Due to such poisoning, the reactor reached a power output of only 30MW thermal. Due to this, the operators removed most of the control rods in order to bring the power back up. And by 00:39, power came back to around 160MW thermal.

At 01:05, as part of the test, the operators turned on 2 additional main circulation pumps (MCP). However, this increased coolant flow reduced the overall reactivity, and the operators were once again forced to remove more control rods.

Now, the RBMK reactor had a serious design flaw — its positive void coefficient. This meant that the steam bubbles (voids) intensified the reactivity as it absorbs less neutrons than water.

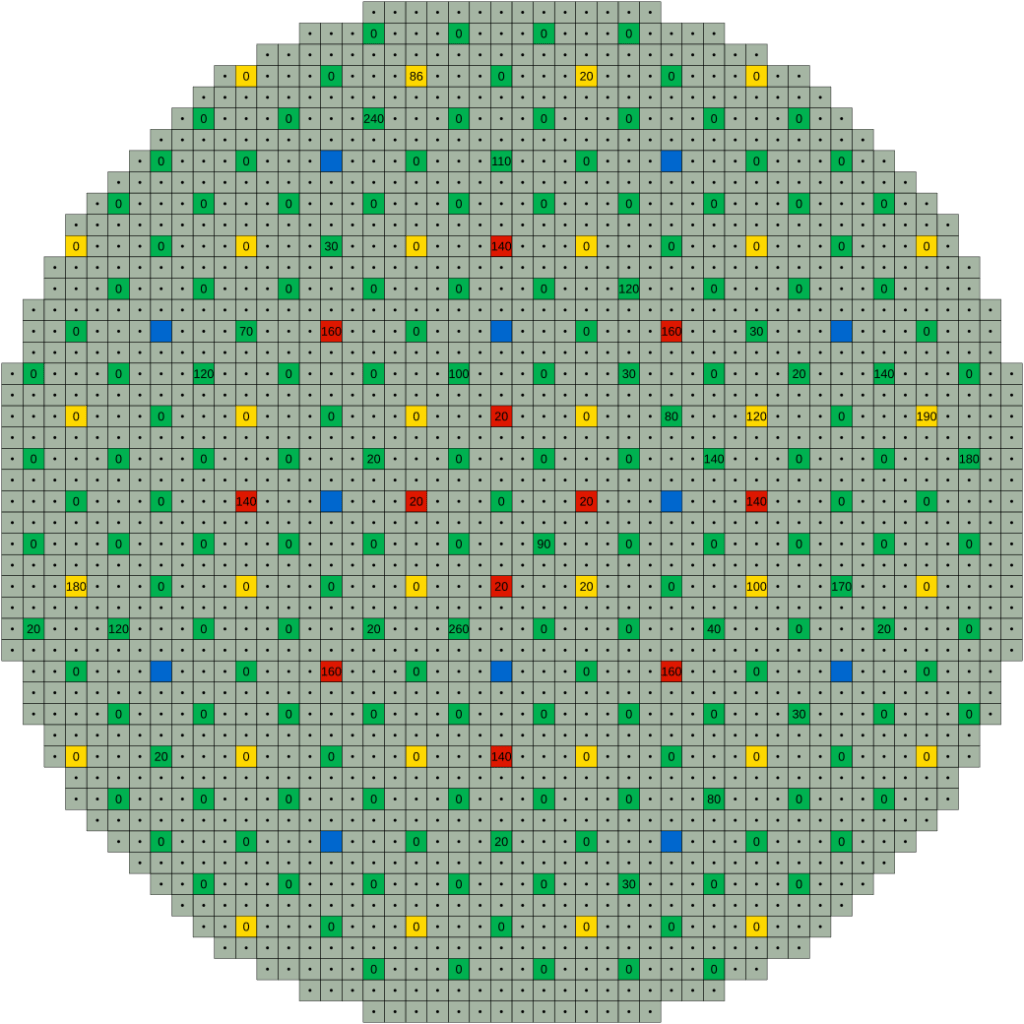

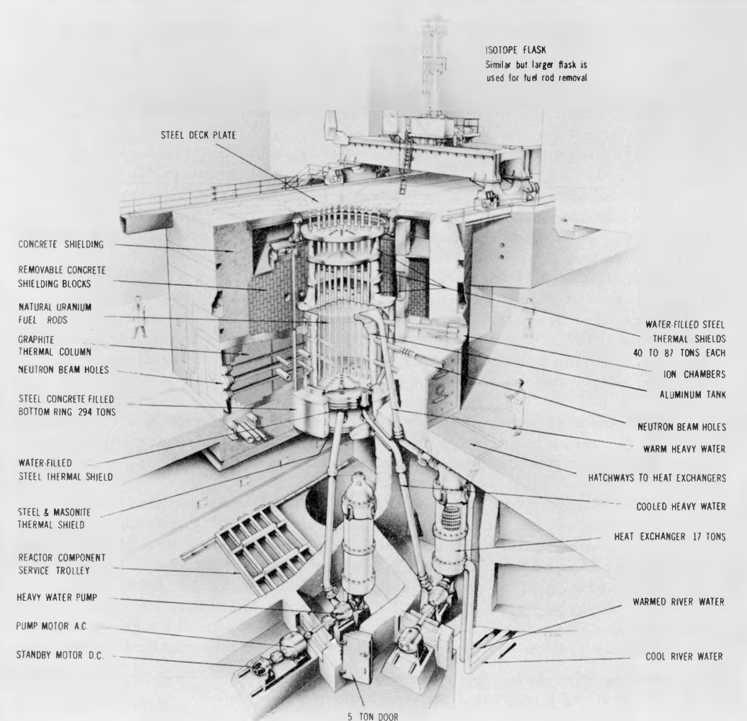

Blue: neutron detectors (12)

Green: control rods (167)

Yellow: short control rods from below reactor (32)

Red: automatic control rods (12)

Grey: pressure tubes with fuel rods (1661)

At 01:23:40, the A3-5 (SCRAM) was pressed. Usually, when a SCRAM procedure is initiated, all the control rods would fully insert into the core within a few seconds. However, the RBMK-1000’s SCRAM sequence fully inserted the rods in 20-30 seconds, way too slow. Additionally, even though most of the control rod was made with neutron-absorbing materials, some of the control rod was made of graphite, which increases reactivity (A common misconception is that only the tips of the control rod were made of graphite of only 6 inches. However, this is not true, as a good 4.55M of the control rod were made of graphite. More on this another time.)

Due to these factors, the A3-5 sequence, which was supposed to save the reactor, instead resulted in a power surge, leading to a serious of explosions that made the lid of the reactor flip upside down. The first explosion ruptured fuel channels and severed the coolant lines. The remaining coolants then flashed into steam and escaped the reactor core. This resulted in more power, and a steam explosion powerful enough to eject radioactive materials into the air and had the power of 225 tons of TNT. However, this 2nd explosion also stopped the nuclear chain reaction, preventing the situation from getting any worse.

That’s it for today kids. Next time, we’ll learn about the misconceptions of this disaster. dont get covid kids.

Leave a comment