Hi kids, today we’ll be talking about the design of the RBMK-1000. Please do add yourself to the email subscribes as it took me forever to research this…

Because this is quite the complicated topic, I regret to say that you will be seeing at only a limited amount of Konata emojis…

Introduction

First, there are few things to understand about the RBMK-1000s design that we need to point out as it is uncommon in other reactor designs such as the PWRs.

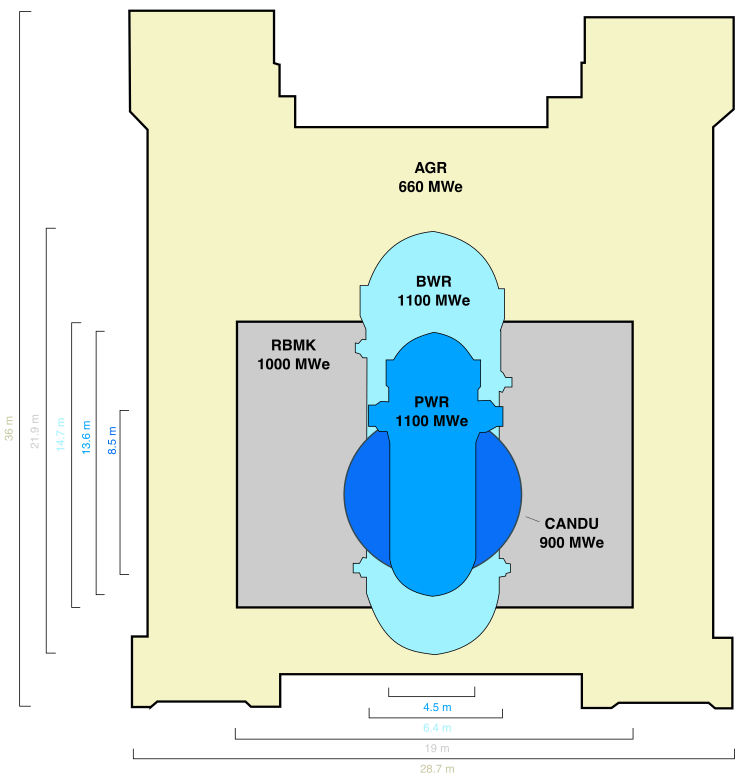

Unlike most reactors like the BWR and the PWR, the RBMK’s reactor vessel is shaped like a rectangle instead of a cylinder.

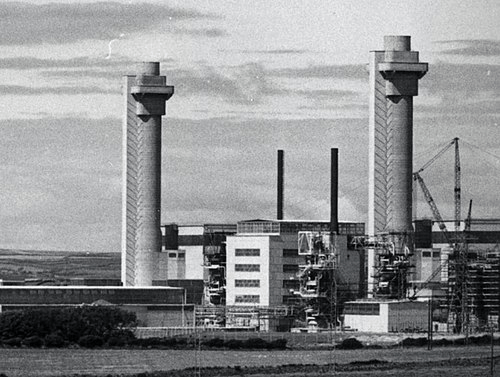

There are 4 reasons for this decision. First, unlike a PWR or a BWR which consists of a large, single pressure vessel, the RBMK used around 1,700 individual pressure tubes running vertically through a large block of graphite moderator. The graphite is stacked like a rectangle for structural stability and to arrange the fuel channels in a square grid, which leads us to our 2nd reason, modular construction. This design allows fuel channels, control rods, and instrumentation to be positioned at fixed intervals. In addition, this layout also makes online refueling easier, as the refueling machines move on rails above the reactor and can reach each channel in the rectangular grid (RBMK is one of only 3 major reactor types capable of online refueling, the other being Canada’s CANDU and the British AGR).

Thirdly, the RBMK was designed for very high thermal power for the time, up to 3,200 MW thermal. A square-shaped graphite block made it possible to build a larger core volume than cylindrical designs, without requiring a huge, forged pressure vessel, which the USSR was incapable of manufacturing at that time period. And finally, the RBMK design was not only made for electrical power generation, but also for plutonium production for the country’s nuclear arsenal, which required high power (This is the reason why when western reactors such as the PWR was capable of generating only a few hundred megawatts electrical, while the RBMK could produce up to a thousand).

Another thing to understand is that the RBMK-1000, interestingly, uses both light water and graphite as moderation (light water is also used for cooling purposes). By this time, most western nations have already moved on from graphite moderated reactors. However, the Soviets still went with graphite as graphite is an excellent moderator. Unlike light water, which moderates and absorbs neutrons, graphite only slows them down. This means a graphite-moderated reactor could run on natural uranium or very low enriched uranium — as enriching Uranium is extremely expensive.

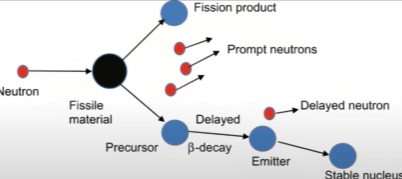

It’s crucial to understand the βeff value, representing the effective fraction of delayed neutrons (delayed neutrons are neutrons released milliseconds to minutes after the initial fission process). These come from neutron-rich fission products undergoing a beta decay chain, which emit a neutron instead of a gamma emission (gamma emission is when an unstable atomic nucleus releases excess energy).

1. The Control Rods

We’ll talk about the control rods of the RBMK design. According to Section 2.2 of the INSAG-7 report, the control rods and the safety rods of an RBMK reactor are mostly inserted from above, except 24 shorter rods which are inserted from the bottom for flattening the power distribution (in a reactor core, no matter its design, the neutron flux of the reactor is usually not uniform. Typically, the center of the core is hotter, while the edges run cooler. This is called a peaked power distribution. To avoid local overheating and to get maximum, safe use of the fuel, operators will attempt to make the power spread out evenly across the core, a process known as ‘power flattening’).

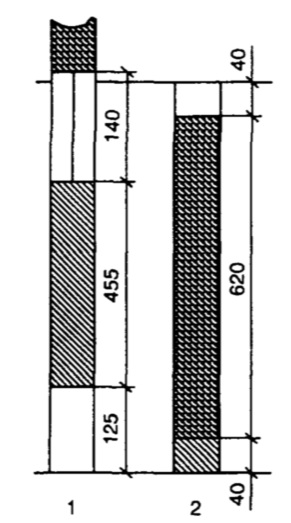

The photo above, shows the control rods of the RBMK-1000 reactor. The diagram labeled ‘1’ is when the rod is withdrawn, and ‘2’ is when the rod is inserted. Many people would question on why the Soviet designers put graphite — a moderator that accelerates reaction — on a control rod, which is supposed to slow down the reaction. Ironically, this graphite part of the control rod was added as a safety/performance feature. As mentioned before, water is also a neutron-absorber, and when the control rod is fully withdrawn, neutron-absorbing boron, with neutron-absorbing water, which is not good. So, the reactor needed something to be there when the control rod was withdrawn, to make sure that the water was not absorbing too many neutrons so that it would slow down reactivity, and the Soviet engineers decided that graphite was the one.

**It is very important to note that despite HBO’s miniseries depicting the Chernobyl disaster, it is not just the ‘tip’ of the control rods that were equipped with the graphite displacers, but rather an entire 455cm of the control rod was made of such graphite displacer.

The graph above by ‘Vlogbrothers’ shows the control rods in their withdrawn state (The red part is the boron absorbers). As we can see, the graphite displacers are made so that they are a little bit shorter than the fuel rods, and in that space, there is a little bit of water remaining. So, you will get a good neutron flux, as it is evenly distributing throughout the reactor.

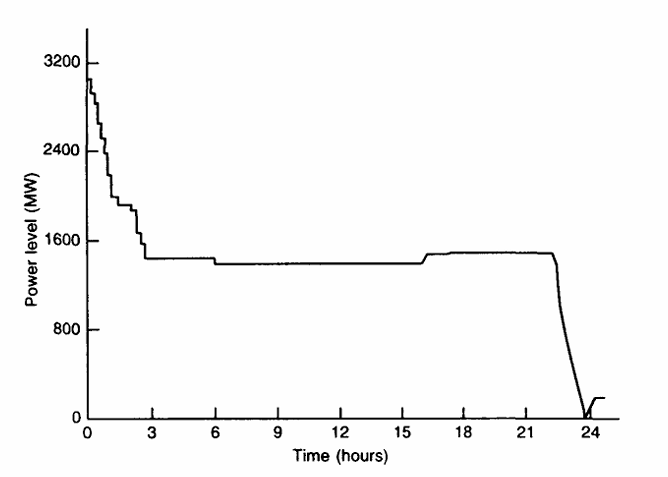

The graph above shows change in power level with time (from initiation of the power reduction) during the Chernobyl accident.

This design did come at a serious disadvantage, shown at the Chernobyl disaster of 1986. At the night of the accident, due to reactor poisoning (when there is too much of neutron-absorbing Xenon-135), power output which was supposed to be 700MW thermal, dropped to just 30MW thermal. To combat this sudden power drop, the operators withdrew most, if not all, of the control rods. Later on, when the operators engaged the A3-5 (SCRAM) sequence, the balance of neutron flux shifted heavily downward, as the graphite moderators slowly creeped down (the RBMK’s SCRAM speed was relatively slow, as it took 18 seconds for control rods to go from withdrawn to fully inserted) the water displaced at the bottom row of the moderator was gone. This led to an overheating of this localized part of the reactor, increasing neutron flux in that part, resulting in a power surge. Due to this power surge, multiple components of the reactor broke down, so the control rods were stuck in that dangerous position, resulting in the explosion.

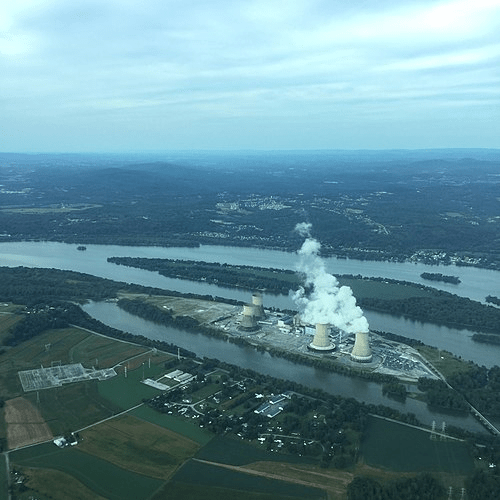

2. The Coolants and ‘Containment’ System

According to section 2.9 of the INSAG-7 report, the RBMK-1000 reactor includes two independent primary coolant loops, which each cools half of the reactor. Each loop is made of four primary coolant pumps. Three of those pumps are used for normal operation, and the fourth standing-by as a backup. Each pump has a capacity of 5500 to 12000 m³/h. Out of the 8 pumps, 4 were powered by the turbine and 4 received power from an external power source.

In PWRs, the coolant is pressurized, preventing it from boiling off, and passes through the core. This coolant then passes through the steam generator through a pipe (that does not directly come in contact with the contents of the steam generator), boiling the water surrounding it, and turning it into steam. However, a RBMK or a BWR does not have this kind of system. Instead, the coolant (usually light water) passes through the core and boils off directly into steam. Under normal conditions in a RBMK reactor, such coolant will enter the core at around 270°C and exit at around 284°C. During the accident at Chernobyl, the use of all eight pumps increased the coolant flow rate above that under normal conditions, reducing the steam content of the core that was already low. More water flow meant lower steam (void) production at the start of the test, resulting in low reactivity.

Due to the RBMK’s positive void coefficient and the low number of voids being produced, the operators had to withdraw more control rods to compensate. Later on, the pumps began to slow down after the turbine trip, reducing coolant flow. This meant more boiling, and more voids, which resulted in a positive reactivity insertion. This led to the core power to rise dangerously, another cause of the Chernobyl accident.

We usually think of the RBMK as ‘unsafe’ for several reasons, one being that there is no containment structure. However, the RBMK does indeed have a containment, but just to protect against the rupture of the primary circuit boundary. According to section 2.10 of INSAG-7, “RBMK reactors have ‘localized’ containments. That is, separate parts of the reactor and coolant circuit are enclosed in individual containment spaces,”. Simply said, the ‘containment’ of the RBMK-1000 did have some kind of containment system to a limited extent that was not nearly enough as the Western counterparts and mainly managed steam pressure relief.

3. The Void Coefficient of Reactivity

Let’s first understand what the void coefficient of reactivity is. In a water-cooled reactor, the coolant (water) can boil into steam bubbles. These bubbles are called voids (empty space where liquid water used to be). The void coefficient describes how the reactor’s reactivity changes when voids (steam bubbles) appear in the coolant. This is calculated by:

αv=Δv / Δρ, where:

Δρ = change in reactivity

Δv = change in void fraction (steam bubbles)

Now both you and I probably don’t understand this math formula. Basically, its a question of; “Does the chain reaction speed up or down when water boils?”

Through this equation, we can categorize a reactor’s void coefficient into two categories: Positive and Negative void coefficient. Negative Void Coefficient is known to be safer, as when voids form, reactivity will decrease, which acts like a self-stabilizer. However, in a RBMK, there is positive void coefficient present, which means when voids form, reactivity will increase. This means less absorption of neutrons, and the chain reaction speeds up, like a positive feedback loop. This is important as a large positive void coefficient like the RBMK’s will make the reactor unstable at low power, one of the key factors that led to the Chernobyl disaster.

Now, we all have asked the same question. Why didn’t the Soviet designers just fix the void coefficient of reactivity problem? Why not make the reactor much safer? The simple answer is that they could have, but it would sacrifice the very things the Soviets wanted from the RBMK. Additionally, the RBMK was designed with a positive void coefficient in mind.

There are several reasons why they did not remove the positive void coefficient. First, removing this would have meant using higher-enriched uranium fuel, so the reactor could tolerate water moderation without instability. However, enrichment was expensive, and the Soviets wanted cheap, rapid reactor deployment. Furthermore, when the first design of the RBMK rolled out, designers spent years trying to lower the cost of the electricity produced. If they raised enrichment, fuel costs went up, and the “cheap electricity” advantage was gone.

As mentioned, several times before, the RBMK was made for dual-use purposes. Low-enriched Uranium, short fuel cycles, and online refueling made the RBMKs perfect for plutonium production, as well as keeping graphite as the moderator and water as the coolant, but a positive void coefficient was inevitable.

Lastly, the USSR did not have the technology to make huge, forged steel pressure vessels like those used in the west at that time. A channel-type design was more practical. This unavoidably led to the increase in the positive void effect.

4. SKALA

Even with a thousand operators, you can’t monitor all the thousands of parameters that are present in a RBMK. Thus, a specialized computer was needed. The first machine of the kind was the KARAT system of the Beloyarsk nuclear power plant, but a much bigger system was needed for RBMK reactors. In the 1960s, the Soviets possessed a few systems that could handle such tasks, one of them being the VNIIEM-3.

Following further research, a newer version — named the V-3M — was developed. SKALA collected information like neutron flux, coolant pressure and temperature, control rod positions, turbine parameters, and more. It also showed these inputs to the operators via data graphics, early graphical displays, and early warnings of parameter deviations.

According to section 1-4.3.2 of the INSAG-7 report, “The system was designed to calculate the basic reactor parameters every 5 min, this period being determined by the power of the V-3M type computer.” However, it looked like the computer faced some issues as well, as later on, the report suggests that, “However, the DREG program does not record important reactor parameters, such as power, reactivity and channel coolant flow rates. It records the position of only nine of the 211 RCPS rods, including one rod from each of the three automatic control groups.” (The DREG program was one of the diagnostic/analysis routines built into SKALA, and it stands for ‘Dynamic Reactor Graph’)

5. The ‘Indestructible’ RBMK

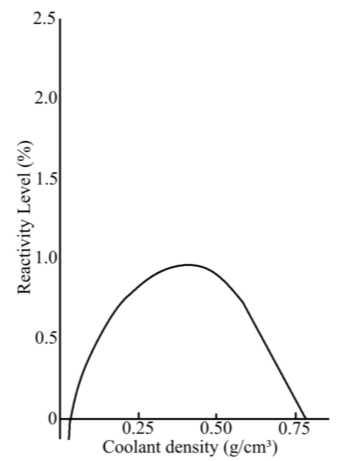

This part will most likely the most interesting part of this post. Before the Chernobyl disaster, the Soviets believed that it was impossible for the RBMK to explode. After the opening of the first RBMK at Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant, the Soviets decided to conduct a test using both experimental data and some computer programs to calculate the effect of water boiling on the reactivity. The results were as follows:

This graph shows that as steam content increased, the reactivity increased. A positive void coefficient. However, the same calculation also suggested that this was valid up until around half the coolant had boiled off. After that point, increase in steam would lead the positive void coefficient became less powerful, and when the steam content approached zero, it became a negative void coefficient. In other words, the calculations showed that even in a situation where all the water had boiled off, the reactor would shut itself down.

After the Chernobyl disaster, the Kachardov Institute decided to run a test at ChNPP to demonstrate that the explosion was not due to a design flaw or such. The reactors were in shut down for months, with little to no decay heat. So, all the operators needed to do for this experiment was to drain the water in the core and observe how it affected reactivity.

Instead of the reactivity decreasing overtime, the reactivity actually increased. By the time half of the coolant has been drained, the reactivity was increasing without stopping, with a βeff value of 5, and the experiment was finally terminated.

The graph above, by ‘That Chernobyl Guy’ on YouTube shows the original calculation conducted before the Chernobyl disaster (black) versus the calculation conducted after the Chernobyl disaster (Red)

So, the question arose. Was the calculation wrong from the first place? The short answer is no. They simply did not think of the changing conditions of the RBMK. When a RBMK reactor starts up fresh with fresh fuel and additional absorbers, the void coefficient of reactivity is in fact, negative. However, as the additional absorbers are replaced with fuel while the rest continues to burn up, the void coefficient of reactivity becomes increasingly positive.

Operators of the RBMK were trained under the assumption that emergency systems, control rods, safety procedures and that calculation, would prevent any catastrophic outcomes such as explosions. The possibility of a reactor blast was not openly discussed — they relied on the trust that these safety mechanisms, as designed, were sufficient. The bell-curve void effect graph remains a symbol of unchecked, optimistic calculations, that eventually led to the downfall of the RBMK.

“Because reactors are designed with operating characteristics and safety features intended to prevent catastrophic failure modes […] The RBMK was indeed designed that way.”

-NumbSurprise, Reddit

I started writing this at 7:30PM and now it’s 1:10AM in the morning. Good night kids.

please subscribe 4 emails

Leave a comment