Hi kids, today we’ll be looking at Russia’s floating nuclear reactor.

The Ship and the Reactor

The Akademik Lomonsov (Russian: Академик Ломоносов) is the one and only floating nuclear reactor in the world. The ship features 2 KLT-40S PWR reactors, capable of generating up to 35MW of electricity each, and is capable of generating 150MW thermal. Both units started construction on the 15th of April 2007 and first connected to the grid on December 19, 2019. The KLT-40 family of nuclear reactors comes from the OK-150 and OK-900 ship reactors.

KLT-40 were developed to power the Taymyr-class icebreakers (KLT-40M, 171 MWt) and the LASH carrier Sevmorput (KLT-40, 135 MWt), and uses 30-40% or 90% enriched uranium, way higher than the RBMK’s 2-3%. This is because unlike the RBMK, which is big and could be refueled on the fly, which means the fuel doesn’t need to be enriched very high. However, a shipborne or a floating nuclear reactor like the KLT-40 is small, so better enriched uranium is required to compensate, and expected to operate for years without refueling, so core life extends. Rosatom states that this new reactor does not have anything in common with the RBMK and incorporates all the state-of-the-art guidelines in the IAEA’s INSAG-3 article. As for the ship itself, has a length of 144 meters (472 ft) and width of 30 meters (98 ft). It has a displacement of 21,500t and a crew of 69 people. It will have a crew of about 300 people.

Why do we need a floating nuclear reactor?

The first question we will all ask is why we even bother to build a floating nuclear power plant. We have perfectly good reactors like Westinghouse’s AP1000 or South Korea’s APR-1400. Even in a sanction country like Russia, VVER-1200 or VVER-1300 models is available for production. Furthermore, Russia could’ve just installed the KLT-40 on land itself. So why do we need the ship?

Russia built the Akademik Lomonsov mainly to provide reliable power to remote and hard-to-reach regions where it would be difficult or uneconomical to build traditional power plants or connect to a national grid (Currently, it’s generating power for the area of Chukotka). There are few main reasons for this.

Firstly, much of northern Russia and the Arctic coast lacks stable energy infrastructure. Villages, ports, military bases, and Russia’s Arctic development programs need constant supply of electricity and heat, especially during the long winters. Floating NPPs can be towed to isolated areas and connect itself into local power grids. Secondly, unlike land-based plants which are either impossible or very difficult to relocate, a floating one can be moved quite easily. If an area suddenly does not need it, the reactor can be towed somewhere else. Thirdly, many Russian Arctic towns depend on imported coal or diesel, which is expensive and logistically difficult to deliver. A floating power plant reduces these dependencies. Finally, permafrost, storms, and unstable ground in the region of Chukotka make it very hard and expensive to build and maintain a NPP on site, while a floating plant avoids these challenges. However, despite these challenges, they actually had one.

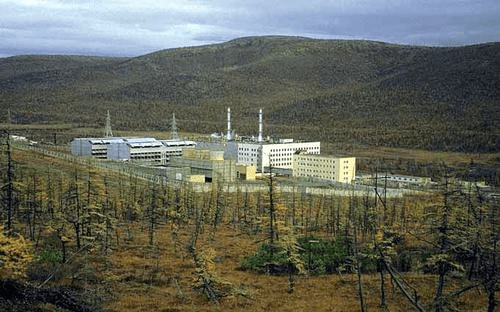

The Bilibino Nuclear Power Plant

The Akademik Lomonsov was built to replace this aging power plant with a rather weird name (sounds similar to the Chinese BiliBili SNS service lol). The plant was named after the town of Bilibino in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, which was named after Yuri Bilibin (1901-1952), a Soviet geologist.

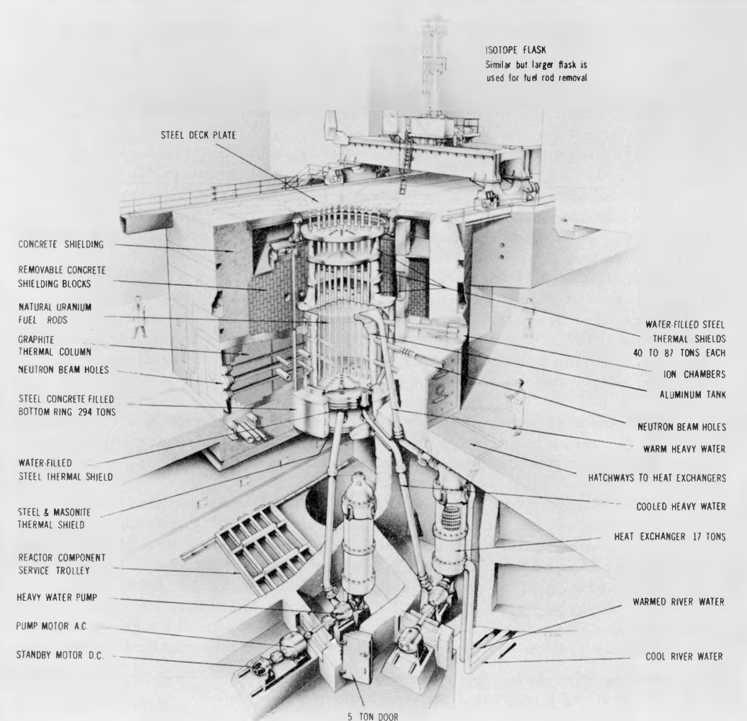

The plant entered commission in 1974 and featured 4 EGP-6 reactors (currently, 1 of those reactors has been decommissioned). It was a small land-based graphite reactor station, basically a scaled down version of the RBMK. But it did use natural circulation instead of pumping. EGP is a Russian acronym that translates to Power Heterogenous Loop reactor and is the world’s smallest running commercial reactor.

As nice as this unique power plant sounds, the plant actually had radiation exposure problems. As of 2012, the EGP-6 reactors exposed personnel and staff on average up to 3.7 mSv/year (yearly limit is 20mSv/year for radiation workers), while normal power plants sit at 1.26 mSv/year

ok bye.

Leave a comment