Hi kids, today we’ll look at the SL-1 nuclear accident in the US.

Background

The Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number 1 (SL-1), operated by Combustion Engineering for the Atomic Energy Commission, initially the Argonne Low Power Reactor (ALPR), was an experimental nuclear reactor at the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS) in Idaho about 40 miles (65 km) west of Idaho Falls, now the Idaho National Laboratory. The reactor ran from 1958 to 1961 and was operated by a total of just 3 people. It is the only accident in the U.S that involved direct human deaths.

The reactor was designed as part of the Army Nuclear Power Program, intended to provide electricity to small, remote military facilities. The project did not get as much funding as other nuclear reactor projects, such as the one for the navy, which was developed at the same facility and later equipped for the world’s first nuclear submarine. Even the air force was funding millions of dollars towards a nuclear-powered jet aircraft.

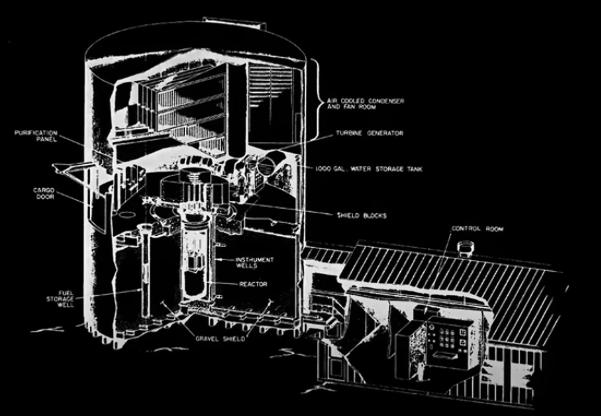

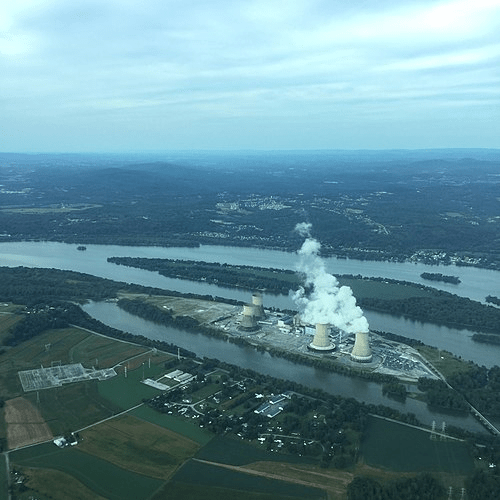

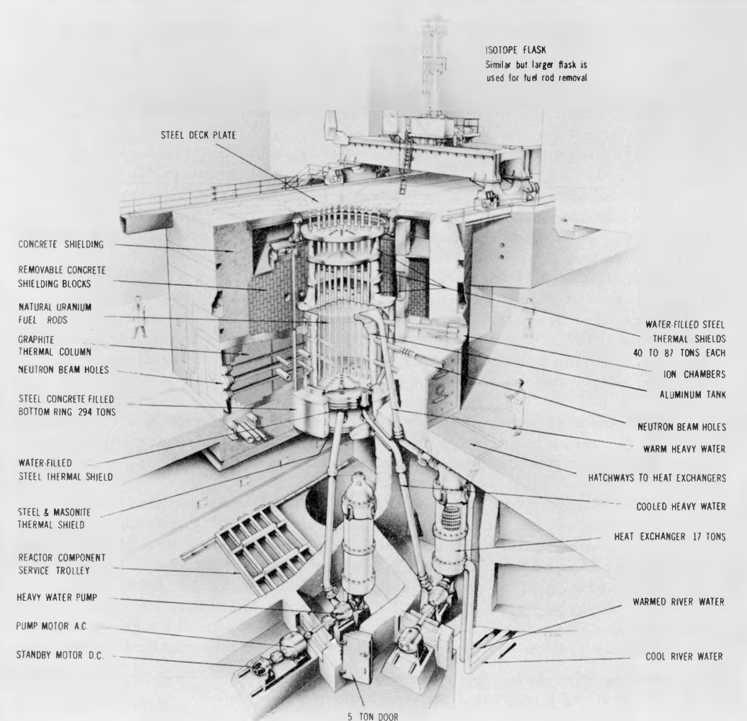

^ Diagram of the SL-1 reactor

The Reactor

The prototype was constructed from July 1957 to July 1958, and went critical on August 11, 1958, and became operational since October 24. The reactor was a BWR (boiling water reactor) and used 93.20% enriched uranium fuel. Unlike larger BWRs, the reactor did not have circulation pumps and rather used natural circulation. The reactor core was designed to hold 59 fuel assemblies, one startup neutron source assembly, and 9 control rods. The reactor vessel is 4.5 feet in diameter and 14.5 feet high. It is surrounded by gravel on the sides and is supported on a concrete pad resting on lava. The following equipment and components are located within the large silo-like structure: the reactor vessel, turbine-generator, heat exchanger and other water-handling

components, air cooled condenser and fans and miscellaneous control equipment. The reactor control room is located in the adjacent support-facilities building. The reactor building was not designed as a leak-tight containment structure.

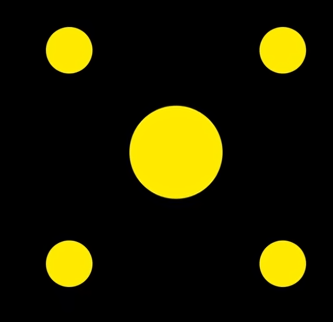

The core at SL-1 had only 40 fuel elements and was controlled by 5 control rods, placed in the shape of a cross: one in the center (Rod Number 9), and four on the periphery of the active core (Rods 1, 3, 5, and 7). In comparison, Chernobyl NPP Unit 4 had 211 control rods.

^ Size of the control rods @ SL-1. Rod #9 was the biggest control rod, where normal NPPs would be all uniform sized control rods.

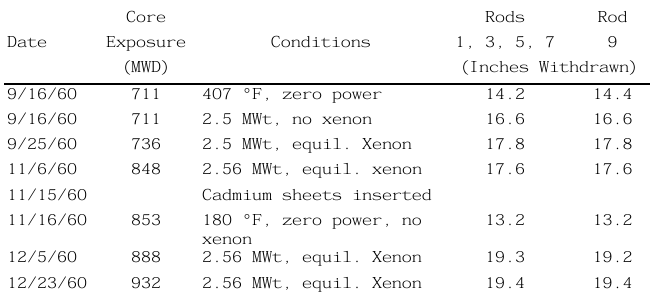

As control rod #9 was so big, it held immense power. Just moving it up/down a few inches could affectively start-up or shut down the reactor. Furthermore, these rods had a very bad habit of getting stuck. According to NASA’s Bryan O’Connor, ‘The rods had exhibited stickiness 2% (80 times) of the time movement was attempted.’ In response, the army told its operators to exercise the rods, in order to prevent it from getting stuck in the future.

^ Table of Representative Critical Rod Positions

However, the situation only got worse. 15 days before the disaster, 2 of the control rods had to be hit with pipe wrenches to get them loose.

The Accident

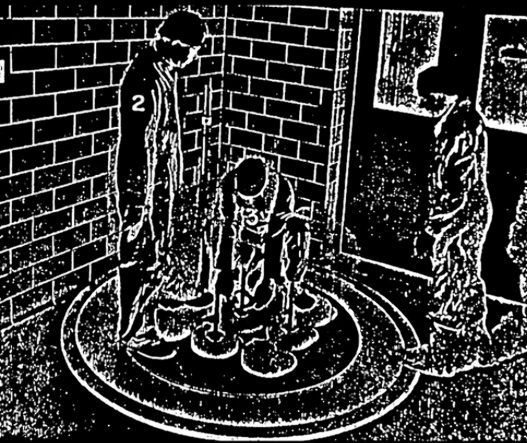

On January 3rd, 1961, 9:01PM MST, one of the three operators withdrew the central control rod #9 as part of a routine maintenance. The rod was meant to be removed by just 4 inches (10.16cm). However, the rod was removed too much by an extra 16 inches, and within 4 milliseconds, the core power level reached 20 GW, 10,000,000% of its normal operating limit.

^ Diagram of the operators withdrawing the control rods on January 3rd, the date of the accident.

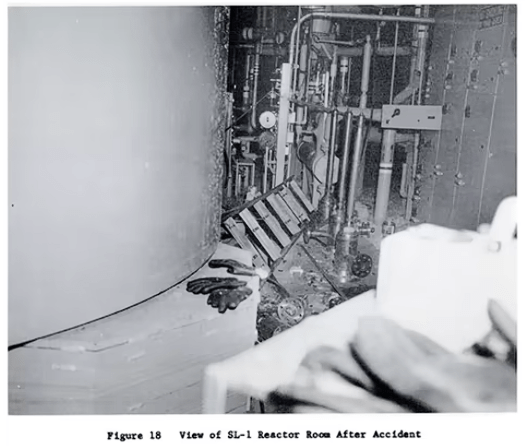

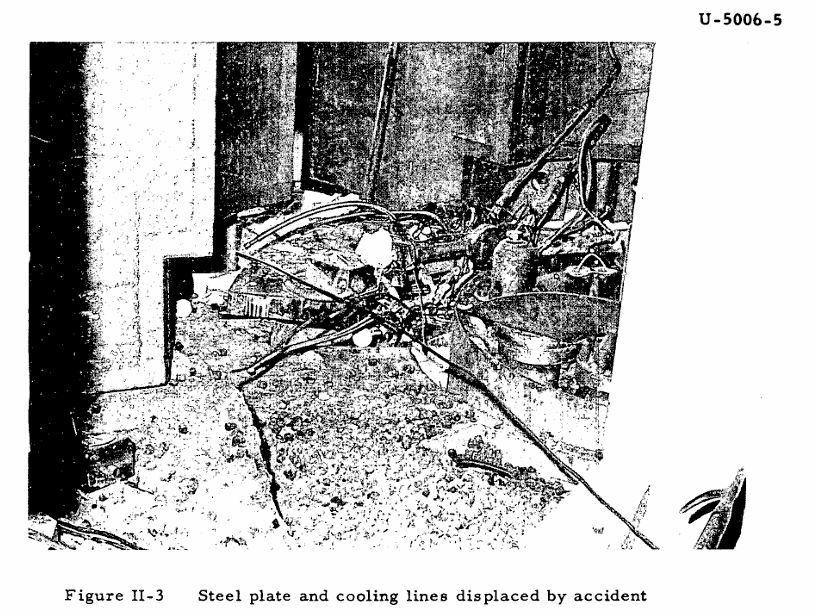

The intense heat from the nuclear reaction expanded the water inside the core, producing extreme water hammer and causing water, steam, reactor components, debris, and fuel to vent from the top of the reactor. As the water struck the top of the reactor vessel, it propelled the vessel to the ceiling of the reactor room. A supervisor who had been on top of the reactor lid was impaled by an expelled control rod shield plug and pinned to the ceiling. Other materials struck the two other operators, mortally injuring them as well. The expansion was so powerful that it lifted the entire 12,000kg (26,000lbs) reactor vessel up by over 274cm (9ft).

This disaster was ranked level 4 (accident with local consequences) on the INES nuclear event scale.

Response & Aftermath

6 firefighters from 8 miles away responded to the site. They were not particularly worried on the way, as they have already responded 2 false alarms on the same day. At 9:10PM, when the firefighters arrived at the unguarded gate of the plant, their radiation detectors were blaring. Initial measurements inside the reactor building, according to the final report of SL-1 recovery operation on July 27, 1962, said that the gamma radiation ranged from 20 to 100 roentgens per hour (R/hr). However, a report by ‘What is nuclear?’ claims that emergency responders faced levels up to 500 R/hr during their initial assessments, and were permitted only brief, one-minute entries due to the high radiation conditions.

At 10:45PM, when the first group of 5 firefighters arrived, they found 2 heavily mutilated men. Byrnes was lying on the ground, dead. McKinley was moaning nearby. Both were wet with irradiated water. 15 minutes later, McKinley was dead. The third operator, Legg, was found impaled by control rod #7 to the top of the ceiling, barely recognizable. More on these men later.

Approximately 22 individuals were involved in the recovery efforts received whole-body radiation doses ranging from 3 to 27 R. The bodies of the three operators were highly contaminated, with one body emitting over 1500 R/hr.

The accident released about 1,100 curies (41 TBq) of fission products into the atmosphere, including the isotopes of xenon, isotopes of krypton, strontium-91, and yttrium-91 detected in the tiny town of Atomic City, Idaho. It also released about 80 curies (3.0 TBq) of iodine-131. This was not considered significant, due to the reactor’s location in the remote high desert of Eastern Idaho.

The Cause

Of course, the cause of this disaster is simple. The reactor design causing the control rods to frequently jam and operator error. But why did the operator remove the control rod above 4 inches? Sure, the operator could’ve just simply spaced out, but this does not make sense. All operators know that accidentally moving the rod too much could end all their lives. So much so, that some joked about yanking the central rod out when the Russians invades.

At first, it was believed that the central control rod #9, weighing in at 85 lbs (~38kg), could not be removed fast enough that an explosion would occur. So, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commision (AEC)’s Idaho Operations Office conducted an experiment to see if it was possible. In conclusion, it was completely possible for an operator to reach the 20-inch final position before steam generation terminated the power excursion. The study further showed that the 20-inch withdraw likely was not result of trying to free a stuck control rod.

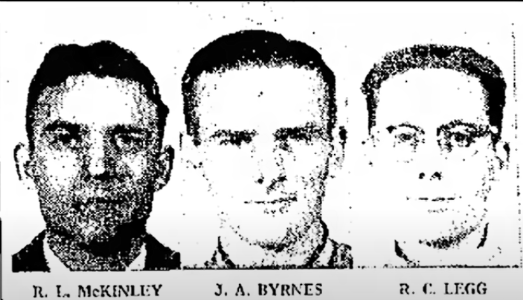

If the 20-inch final position couldn’t have been accidental, then what caused it? There is a story that claimed that this accident was a murder-suicide accident. First, let’s get to know the 3 operators. Richard Leroy McKinley was an electronics technician and was 27 years old at the time of the accident. John A. Byrnes was also 27, and was the team leader of the crew, and had the most experience, and is suspected to be the one who pulled the central control rod #9. Finally, Richard C. Legg was 26 years old and was a navy-trained civilian mechanical maintenance technician.

These three men did not get along well. There was a possible love triangle, involving Byrnes and Legg and a woman (possibly Brynes’ wife or girlfriend). Brynes may have harbored intense resentment towards Legg or both men and was reportedly involved in a fistfight against Legg in a prostitute bar. Some sources further show that at least one or more of them were mentally unstable or under extreme psychological stress.

Byrnes was reportedly suffering from marital issues, and an internal rumor claimed he had found out about an affair between his wife and Legg. McKinley is generally viewed as uninvolved in the conflict, with some saying that he was just “in the wrong place at the wrong time”.

The AEC and military investigators never officially concluded that the accident was intentional. However, they did not rule it out either. The accident investigation included psychological autopsies, rare for the time. Some internal reports leaned towards a deliberate act, but this was politically radioactive and suppressed from public release.

Leave a comment