hi kids, today we’ll talk about the two accidents at Chalk River Laboratories.

Background

Chalk River Laboratories were drawn up in the 1940s, during the Second World War. It is located near the town of Chalk River, Ontario (Canada). Though the site did supply the United States with plutonium during the Second World War, contributing to the Manhattan Project, it was mostly dedicated to the investigation of nuclear power and peaceful uses of the atom. The facility erected in 1942 by the British and the Canadian nuclear researchers. The site opened in 1944 and put the first nuclear reactor outside of the United States into operation in September 1945.

The reactor was named Zero Energy Experimental Pile (ZEEP). The reactor was designed by the Canadians, the British, and French scientists to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons for the war effort. ZEEP was a heavy water reactor, and was designed to use unenriched, natural uranium. ZEEP was used for basic research until 1970 and was eventually decommissioned by 1973.

The NRX Reactor

The National Research Experimental (NRX) reactor was the successor to the ZEEP reactor and came into operation in 1947. The reactor was capable of operating at 10MW thermal, which was later increased to 42MW thermal by 1954. The NRX reactor was also heavy water-moderated reactor. It is incorporated in a sealed vertical aluminum vessel with a diameter of 8 meters (26 ft) and a height of 3 meters (9.8ft).

The purpose of the reactor was to produce isotopes, test materials, and support early reactor physics studies. At the time, NRX was the most powerful and complex research reactor in the world but also lacked the safety interlocks and fail-safe control that we have in modern reactors.

According to AECL’s report DR-32 by W.B. Lewis, normal sequence of the operations to start up the reactor is as follows:

(1) to set the level of the heavy water at a predetermined level somewhat below that required for criticality;

(2) to raise the shut-off rods;

(3) to raise the one control rod which gives only a fine control equivalent to about 10 cm height of heavy water

(4) to raise the level of the heavy water slowly to that predicted for criticality.

There was a total of 12 shut-off rods. These rods were electrically interconnected in “banks” or groups which operated together. For comparison, in a modern nuclear reactor, an operator would select an individual control rod and choose to either insert it or remove the rod. In the NRX, there were 6 banks to control the rods:

Bank 1 would be brought up by push button 1 at the control desk. The remainder were brought up in the sequence of the bank numbers by automatic interconnection after pressing push button 2.

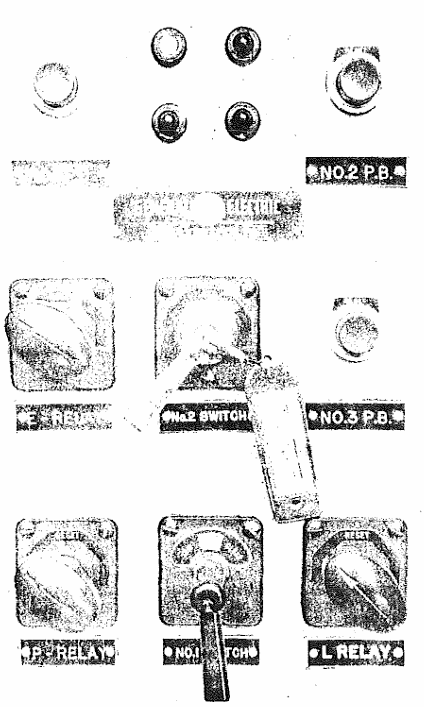

^ Central Panel on control desk

1952 Accident

The NRX reactor at the time of the 1952 accident was a 30MW heavy-water-moderated, light-water-cooled reactor. On 12 December 1952, the operators conducted a test at low power. During this time, a number of the senior staff of the operations department were absent. The test was to conduct measurements of the reactor reactivity at low power, comparing the reactivity of long-irradiated rods with that of fresh rods. To achieve this test, some rods were without water and substitute air cooling. Only one rod was air-cooled and that was a fresh unirradiated rod. The reactor was offline for several days, to leave some transient poison.

During the event, the accident began with an operator error in the basement who mistakenly opened three or four bypass valves on the shut-off-rod air system, causing those rods to rise when the reactor was shut down. The supervisor assumed that the rods would come back into its original position eventually, but due to some unknown reason of mechanical error, the rods did not return all the way, but just enough to reset the red lights on the control desk.

The supervisor then ordered to press buttons 4 and 1. He meant to say 4 and 3, but 4 and 1 should have been safe as well under normal circumstances, as all the shut-off red lights were out, meaning the shut-off rods were inserted.

By the time the first bank of rods was raised, due to the absence of some control rods and reduced coolant flow, the reactor became prompt critical, where power surged to about 60 – 90 MW, far above its design level of ~30MW. This took a few seconds to be obvious, as there were no alarms.

After the operator noticed the power surge, the operator pressed the SCRAM sequence about 20 seconds after pushing button 1. However, the sequence partially failed, as the control circuitry was damaged by electric overload. Furthermore, three out of four rods failed to insert back into the core because of pneumatic valve malfunctions over the course of 1.5 minute.

In order to combat the still-rising reactor power, the operators decided to do the last-resort option, which was to dump the polymer. In this case, the polymer is the heavy water used for moderation, as no moderation means there won’t be any neutrons to split any more Uranium atoms.

The dump eventually stopped the reaction, but the damage has already been done. A hydrogen explosion blew off several pressure-tube end fittings, the reactor vessel was cracked and deformed, roughly 4,000 cubic meters of radioactive heavy and light water flooded the reactor basement, and several fuel elements disintegrated, and fission products were released into the coolant water.

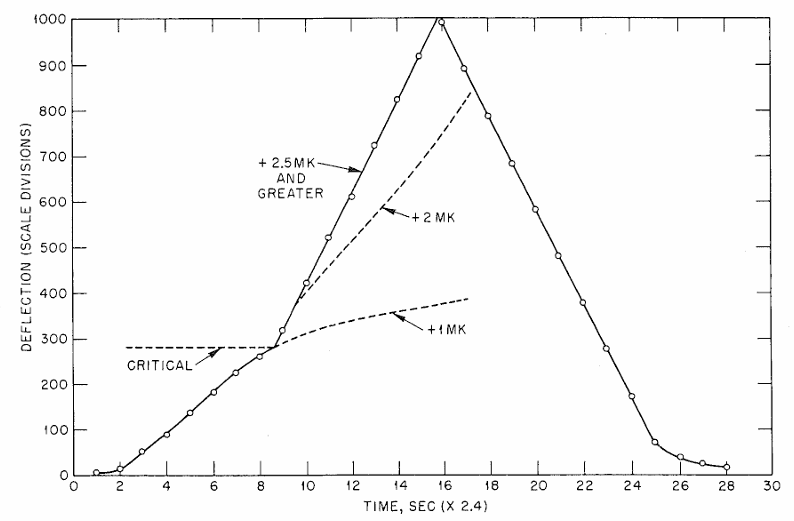

^Expanded trace of power recorder during the power surge with transients from simulator superposed.

The NRU Reactor

The National Research Universal (NRU) reactor was a 135MW nuclear research reactor. The reactor served three main roles; It generated radionuclides used to treat and diagnose people, it provided neutrons for the NRC Canadian Neutron Beam Centre, and it was the test bed for AECL to develop fuels and materials for the CANDU reactor.

In the initial design in 1949 as the successor to the NRX, the reactor was supposed to be a 200 MW reactor fueled by natural, unenriched uranium, which went online in 1957. NRU was later converted to 60 MW with highly enriched uranium in 1964 and later converted again in 1991 to 135MW running on low-enriched uranium

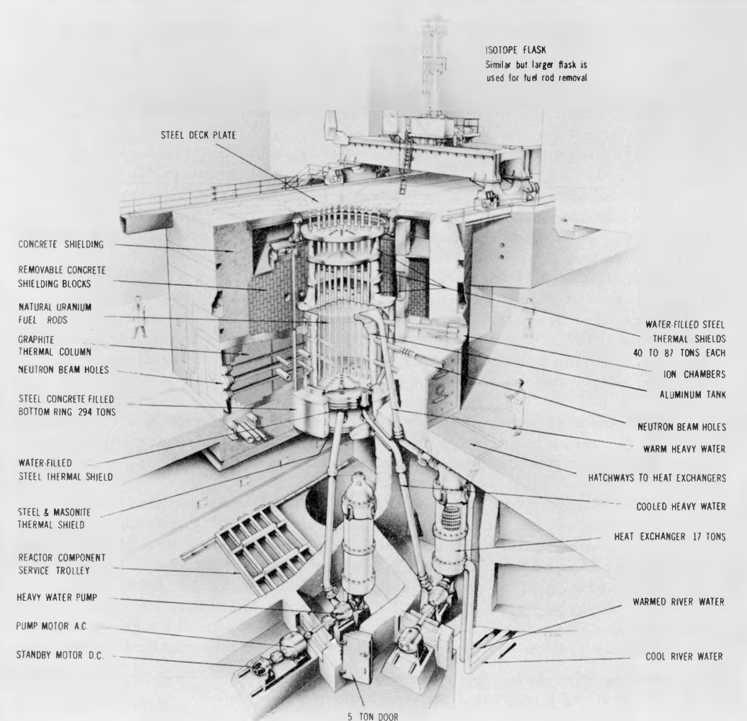

^ Diagram of the NRU reactor

The core was designed in a hex array with 227 openings (sites). These could be filled with fuel roads, experimental loops, isotope production rods, control rods, etc. In the original design, there were 18 control rods and 85 – 95 fuel rods consisting of natural uranium.

1958 NRU Accident

On 24 May 1958, workers were preparing to remove some damaged fuel rods from the core. This would be done by crane, with the removed fuel rod being transferred into a cooling flask filled with water, and then later transferred to a pool. However, during the removal of a rod, the workers realized that the cooling flask that they had prepared did not contain any water. So, the crane operator attempted to put the fuel rod back into the core, where it became jammed, broke, and caught fire.

The whole building was contaminated. The valves of the ventilation system were opened, and a large area outside the building was contaminated. The fire was extinguished by scientists and maintenance men in protective clothing running along the hole in the containment vessel with buckets of wet sand, throwing the sand down when they passed the smoking entrance.

The fire was eventually extinguished, but a sizeable amount of radioactive combustion products had contaminated the interior of the reactor building. The clean-up and repair took around three months, and the reactor came back into operation in August 1958.

Leave a comment