hi kids, today we’ll see how Chernobyl affected NPPs.

Background

Of course, to understand what lessons we have learned from Chernobyl, we have to know what happened at Chernobyl itself. Chernobyl NPP was located near the town of Pripyat, north of the Ukrainian SSR of the former Soviet Union. The explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in April 1986 was the most severe accident in the history of nuclear energy. The accident was caused by a string of design failures, operator error, and also has one of the most misinformation about the accident.

The disaster happened while operators were conducting a safety test of simulating cooling the reactor during an accident in blackout conditions. The cause of the accident is partially due to operator errors but mainly falls on the reactor’s design. Shutting down the reactor in certain conditions, like the ones during the accident, resulted in a power surge, resulting in a steam explosion and meltdown of unit 4.

At 01:05, as part of the test, the operators turned on 2 additional main circulation pumps (MCP). However, this increased coolant flow reduced the overall reactivity, and the operators were forced to remove more control rods.

At 01:23:40, to prevent the accident from spiraling down any further, the A3-5 (SCRAM) was pressed. Usually, when a SCRAM procedure is initiated, all the control rods would fully insert into the core within a few seconds. However, the RBMK-1000’s SCRAM sequence fully inserted the rods in 18 seconds, way too slow. Additionally, even though most of the control rod was made with neutron-absorbing materials, some of the control rod was made of graphite, which increases reactivity (A common misconception is that only the tips of the control rod were made of graphite of only 6 inches. However, this is not true, as an entire 4.5M of the control rod were made of graphite.)

Due to these factors, the A3-5 sequence, which was supposed to save the reactor, instead resulted in a power surge, leading to a serious of explosions that made the lid of the reactor flip upside down. The first explosion ruptured fuel channels and severed the coolant lines. The remaining coolants then flashed into steam and escaped the reactor core. This resulted in more power, and a steam explosion powerful enough to eject radioactive materials into the air and had the power of 225 tons of TNT. However, this 2nd explosion also stopped the nuclear chain reaction, preventing the situation from getting any worse.

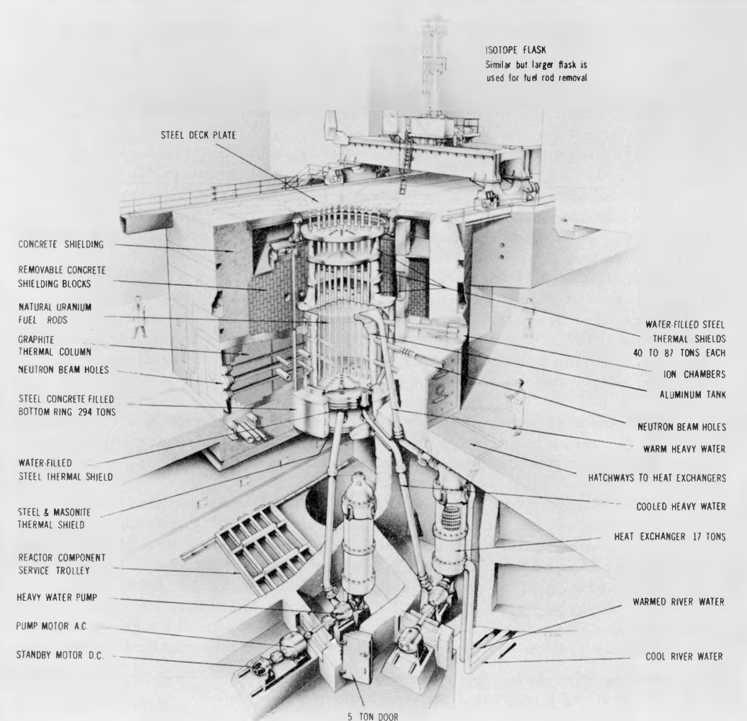

Reactor Design

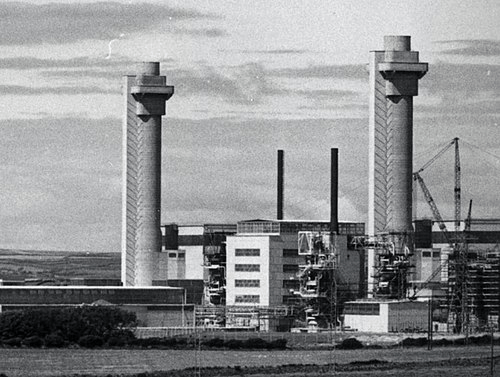

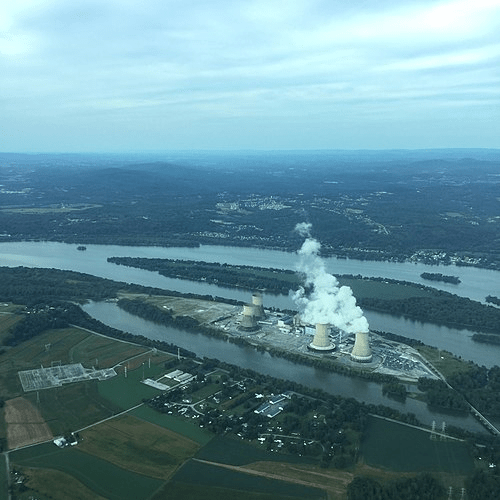

Perhaps the most direct change after Chernobyl was in the physical design of reactors. The Soviet RBMK reactor used at Chernobyl NPP had a number of dangerous features: it was unstable at low power, lacked a proper containment structure, and had a positive void coefficient — meaning that when water boiled away, the reaction sped up instead of slowing down. When operators made mistakes during the test on that fateful day in 1986, these flaws combined to create a runaway chain reaction that couldn’t be stopped.

Modern reactors are built with the exact opposite behavior. They are designed with negative power coefficients, meaning that as power rises, the nuclear reaction naturally slows. This makes sure that any uncontrolled power surge unlikely. Furthermore, all modern nuclear reactors are equipped with redundant shutdown systems, often called SCRAM systems, that automatically insert control rods to absorb enough neutrons to halt nuclear fission within ~2 to 5 seconds. As mentioned, Chernobyl also had such SCRAM sequence, called AZ-5 (A3-5 in Russian, meaning Emergency Protection of the 5th Category) but it was too slow to effectively shut down the reactor in time (~18 secs). In the modern era, any SCRAM sequence slower than 7 seconds are considered unsafe.

(Fun fact: SCRAM stands for safety control rod axe man or safety cut rope axe man, as during the world’s first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, had an actual control rod tied to a rope with a man with an axe standing next to it, so the rods will fall by gravity into the reactor core)

Containment structures became another essential safety feature. RBMK-1000s did not have a containment dome as the reactor was housed in a standard industrial building. Nowadays, reactors are enclosed by thick concrete and steel domes meant to trap radiation, withstand earthquakes, explosions, and even aircraft impacts.

Further generations of reactors such as those models of Generation III+ also use a passive safety system that can operate without electricity or any pilot intervention. For example, some may rely on natural circulation of water or gravity-powered coolant tanks to prevent overheating in case of total power loss.

Different perspectives of Safety

Before 1986, many nuclear operators saw safety as a technical issue, something built into the machines. Chernobyl proved that human behavior was equally critical. The night-shift team conducting the test ignored multiple warning signs and turned off safety systems. Now, operators are trained to follow procedures exactly and to stop operations immediately if conditions become uncertain. Operator training also has changed. Plants now use full-scale simulators that reproduce real-time reactor behavior under normal and accident conditions. Trainees practice normal reactor operations, coordination, and communication.

Chernobyl also revealed on how a nuclear disaster can quickly become a global problem. Radioactive clouds spread across borders within days, affecting other countries. For example, nuclear power plants in Sweden detected abnormally high radiation levels on-site, but nothing was wrong with their reactors. The radiation was coming from the exposed core of the former Unit 4 of the Chernobyl NPP.

In 1994, the Convention on Nuclear Safety was adopted under the IAEA. Two years earlier in 1989, the world’s plant operators had already created the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO). Its goal was to share operational experience, peer reviews, and identify weaknesses before they cause accidents. These two departments now work together with several countries to ensure safety.

The Soviets attempting to hide the accident from the world or even to its own citizens did not help at all. At the time, the nuclear reactors of the USSR were viewed as pride, and admitting a flaw or an accident would be a disaster, so a coverup began. It was only when Swedish scientists detected unusual radiation levels coming from ChNPP that the Soviets announced the accident globally.

To prevent such things from happening again, new rules imposed by the IAEA requires immediate international notification of any significant nuclear event, under the ‘Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident’. Many regions now operate real-time radiation monitoring networks linked across borders. Every facility must also now possess a detailed emergency response plan, including evacuation, communication channels, and emergency responders.

Leave a comment