hi kids, today we’ll see how three mile island (tmi) happend.

Background

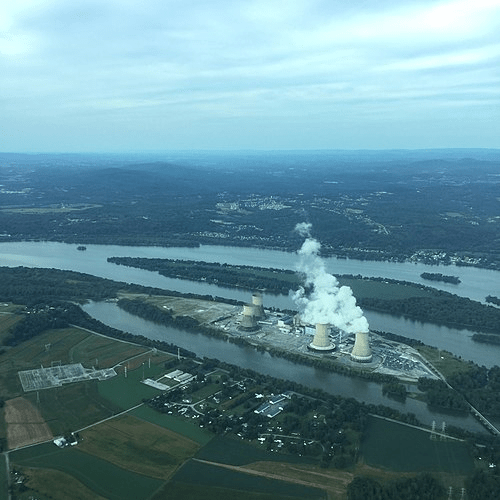

The Three Mile Island Generating Station (TMI) is a former nuclear power plant located in Pennsylvania, United States, near the town of Harrisburg. The plant consists of two total units: TMI-1 and TMI-2. They began construction on May 18, 1968, and November 1, 1969, respectively. Currently, Unit 1 is owned by Constellation Energy — who recently struck a deal with Microsoft to restart Unit 1 to power their data centers — and the partially melted down TMI-2 is owned by EnergySolutions. As of 2009, the site has not been fully decommissioned.

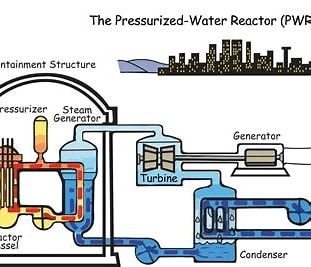

TMI Unit 1 is a pressurized water reactor capable of generating up to 819 MWe. It came online on April 19, 1974, and was licensed to operate for 40 years, but the license was extended by another 20 years in 2009. Unit 1 had a closed-cycle cooling system for its main condenser using two natural draft cooling towers.

^ September 2019 photo of Three Mile Island and Goldsboro, Pennsylvania

TMI Unit 2 was also a pressurized water reactor. TMI-2 was slightly larger with an electrical load capacity of 906MWe. Unit 2 received its operating license on February 8, 1978, and began commercial operation on December 30, 1978. TMI Unit 2 was permanently shut down after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979.

Although it caused no deaths nor injuries, the accident at the Three Mile Island Unit 2 was the worst nuclear incident in U.S. commercial nuclear power history. Unit 2 was fairly new when it partially melted down, as the accident began in the early morning hours of March 28, 1979.

The Accident

At about 4 a.m. on Wednesday, March 28, 1979, TMI-2 experienced a failure in the secondary, non-nuclear section of the plant. A mechanical or electrical failure prevented the main feedwater pumps from sending water to steam generators that remove heat from the reactor core. As a result, the reactor automatically shut down along with the turbines. Immediately after, pressure in the core began to increase.

The initial cause of the accident occurred 11 hours earlier. While attempting to fix a blockage in a condensate polisher (A device used to filter water condensed from steam), the filters cleaning the secondary loop water. The filters are designed to stop minerals and other impurities in the water. Blockages within these filters are common and are usually fixed easily. However, this time, the usual method of forcing the stuck resin out with compressed air was unsuccessful.

The operators decided to blow compressed air into the water and let the force of the water clear the resin. When they forced the resin out, a small amount of water forced its way past a stuck-open check valve and found its way into an instrument airline (A tube that contains and carries a compressed air supply). This would eventually cause the feedwater pumps, condensate booster pumps, and condensate pumps to turn off around 4:00 a.m., which would, in turn, cause a turbine trip.

^ Simple, labeled diagram of a PWR (not necessarily TMI’s).

In order to control the pressure within the reactor, a pilot-operated relief valve (PORV, a valve located at the top of the pressurizer) opened. The valve — in normal circumstances — should’ve have closed automatically when the pressure falls within normal range, but it never did. To make the situation worse, the indications at the control room stated that the valve was indeed closed.

As a result of the opened relief valve, coolant water was pouring out of the valve. As said coolant flowed through the valve, other instruments available to operators provided inadequate information, and no instrument showed how much water covered the core.

^ The pilot-operated relief valve on top of the pressurizer (see arrow) failed to close at the start of the accident. Steam leaked out through the stuck-open valve into the basement of the reactor building at a rate equivalent of some 220 gallons of water per minute, which continued for more than 2 hours and 20 minutes before operators realized that the valve had failed to shut. This was a failure for which the TMI operators had never been trained, and which was not described in their written emergency procedures. This lack of preparation led to a misreading of the symptoms and mistaken responses that

would uncover the reactor core.

When the feedwater pumps tripped, three emergency feedwater pumps started automatically. However, there was a block valve that was closed in each of the two emergency feedwater lines, blocking any water from entering the steam generators. One of the valve’s position lights were blocked by a yellow maintenance tag.

At 5:20 a.m., the primary loop’s four main reactor coolant pumps cavitated as steam bubbles flowed through them instead of water. It was believed that even without the pumps, natural circulation would continue the water movement. However, steam in the system prevented flow through the core, and the water that was supposed to flow through the core increasingly turned into steam.

At 6:00 a.m., only after a new arrival came thanks to shift changes, did they realize that the temperature in the PORV tail pipe and the holding tanks were excessive, and used a block valve to shut off the PORV. But by then, 120,000L (32,000 US GAL.) of coolant water had already leaked from the primary loop. Radiation alarmed blared around 6:45 a.m. The containment building recorded a radiation level of 800 rem/h.

In the end of the accident, due to a series of errors and equipment malfunctions, along with some questionable instrument readings, resulted in loss of reactor coolant, overheating of the core, and damage to the fuel.

Aftermath

Near the vicinity of Three Mile Island, the maximum total increase in radiation at ground level was less than 100 millirem, according to the NRC. This equivalates to a yearly background radiation level absorbed in Denver or Manhattan. However, the amount of radiation actually exposed to the public was low, at less than two millirem per person.

The employees of General Public Utilities (owner of Three Mile Island) were not so lucky, however. According to G. R. Corey of the IAEA report, “Twelve received a dose of between two and three rem; three received a dose of between three and four rem. The maximum allowable dose under NRC regulations is three rem per quarter or an annual average of five rem.”

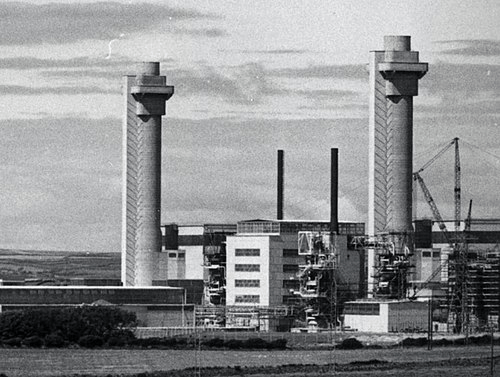

Despite all this, Three Mile Island was not the worst radiation release from an operating reactor. The release in October 1957, during the accident at Windscale in northern England, was far worse. At Windscale, a fire in the graphite core burned for several days, The radiation fallout resulted in some of the milk from cows in the surrounding area showing radioactivity levels at milking time as high as 800,000 picocuries per liter — 40,000 times the levels observed at Three Mile Island.

Initially, GPU planned to repair the reactor and return it into service. However, it was revealed that TMI-2 was too badly damaged and contaminated to resume operations, and the reactor was permanently closed. At the time of the accident, TMI-2 was only online for three months. The cleanup started in August 1979 and ended in December 1993, costing a total $1 billion.

By contrast, the NRC had found some traces of radioactive iodine in their milk after the Three Mile Island accident, but only 20 picocuries per liter which was for too low for the FDA to take any action as their recommended action level was 12,000 picocuries per liter.

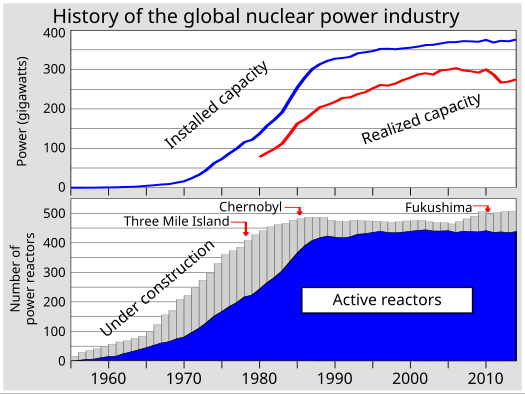

The accident further increased distrust in nuclear power. TMI was already under pressure from protests before the accident to shut down the plant, and we can only imagine how much this increased after the accident.

C. R. Corey stated in the final paragraph of his report, “In closing let me say that we at Commonwealth Edision know that the Three Mile Island accident may slow down the development of nuclear power, but we also know that it does not justify abandonment of the nuclear option. We are firmly dedicated to minimizing the use of oil in the generation of electricity and we shall continue the development of a judicious mix of nuclear and coal-fired generation.”

Leave a comment