hi kids, today we’ll look at the windscale fire.

Background

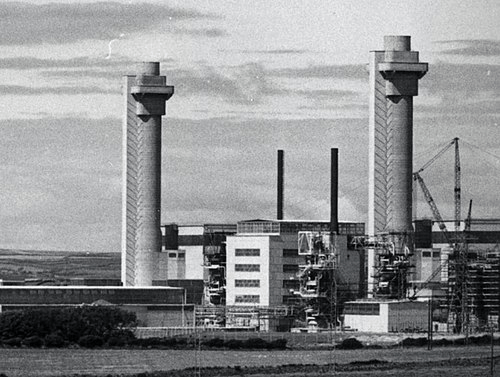

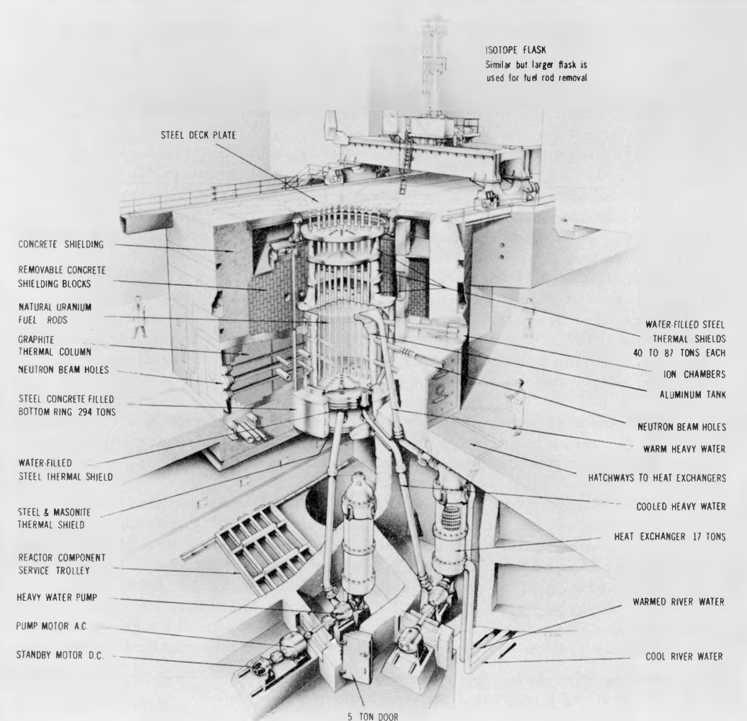

The Windscale Piles were two air-cooled graphite-moderated nuclear reactors on the Windscale nuclear site on the north-west coast of England. The reactors were created as part of the British post-war atomic bomb project and produced weapons-grade plutonium to use in nuclear weapons, which meant that they weren’t primarily built for power production, so the plant did not possess any turbines.

The British had three main points that influence reactor designs: that of the fuel, the moderator, and the coolant. The first choice, that of fuel, was natural uranium, since there were no enrichment plants to produce uranium-235, and no reactors to produce plutonium of uranium-233. This restricted the choice of moderators to heavy water and graphite. Even though the ZEEP reactor used at the Chalk River NRX in Canada had used heavy water, this was not available in the UK. So, the choice was made to make graphite the main moderator. Thus, the UK’s first nuclear reactor, GLEEP, went critical at Harwell on 15 August 1947.

One major problem of the GLEEP was its low output. GLEEP was a research reactor was only capable of 100kW. Even though this was completely fine for experimental works, the production of radioactive isotopes required a more powerful 6,000 kW reactor with higher neutron flux. As a result, the British Experimental Pile Zero (BEPO) was born. The BEPO was a 6MW experimental reactor which was commissioned in 1948.

Back at Windscale, Pile No. 1 went critical in October 1950, but its performance was about 30 per cent below its designed rating. Pile No. 2 went critical in June 1951 and was soon operating at 90 per cent of its designed power.

^ Windscale Piles circa 1956.

At Windscale, major problems emerged during the construction. For the best possible result, the graphite used for the reactor had to be as pure as possible, as any impurities may result to reactor poisoning. Furthermore, a Hungarian American physicist named Eugene Wigner had discovered that graphite, when bombarded by neutrons, suffers dislocations in its structure, causing a build-up of potential energy.

If said potential energy, if allowed to accumulate, may escape spontaneously in a powerful rush of heat. Such events happened in a few instances, as on 7 May 1952, Pile No. 2 experienced a rise in core temperature, despite the fact that the Pile had been shut down. In response, the blowers were started and the Pile cooled down. Another instance was in September 1952, where another increase in temperature was noted while the Pile was shut down. However, this time, smoke was observed coming from the core. Once again, blowers cooled the core down.

Back then, there was only one way to deal with Wigner energy. A process called annealing was to be done at a regular basis at shutdown. The process consisted of deliberately heating the core up above 250C (482F) for a gradual release of said energy throughout the core. This process was done with much success in its earlier days, but as time went on it became increasingly difficult to force the stored energy out.

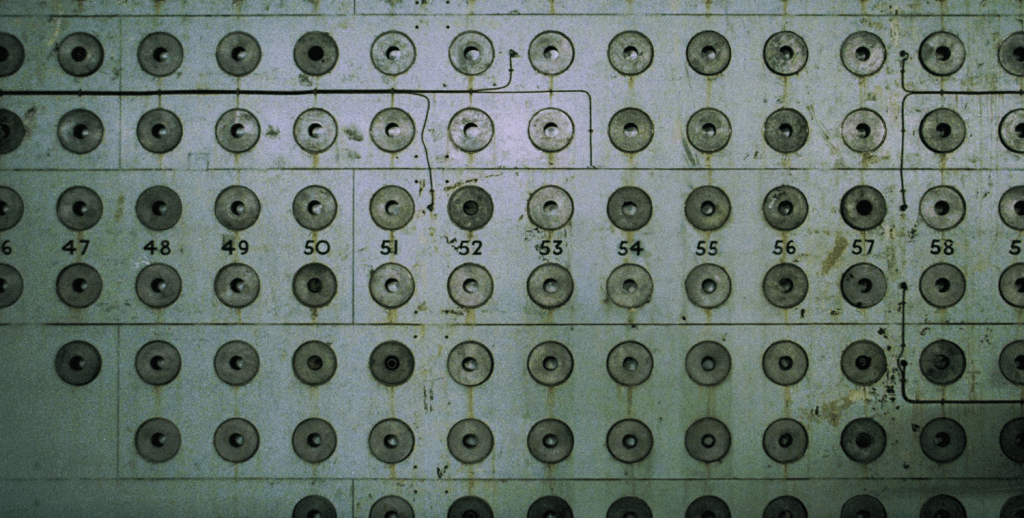

The Accident

On 7 October 1957, Pile 1 of the Windscale Piles reached the 40,000 MWh mark, and it was time for the 9th Wigner release — something like changing your car’s transmission oil. The cycle was known to cause the reactor core to heat up evenly, but during the 9th annealing process, temperatures began falling across the reactor core, except in channel 20/53, where temperature was rising. The operators came to the conclusion that only channel 20/53 was releasing Wigner energy, but none of the others were, and the decision was made that on the morning for a second attempt at a Wigner release. This caused the entire reactor’s temperature to rise, indicating a successful release.

^ Windscale Piles’ Graphite Core Channels

Early in the morning of 10 October, however, something unusual was going on. The temperature of the core was supposed to gradually fall as the Wigner energy release ended, but a thermocouple indicated that the core temperature was instead rising. As this continued, the core temperature reached 400C (750F). In order to combat the temperature, the operators increased the speed of the cooling fan, and radiation detectors in the chimney then indicated a release of radiation, and the operators thought that a uranium cartridge has burst, but in fact, not only did it burst, but caught fire in channel 20/53.

The fans — which were supposed to cool the reactor down — instead fanned the flames. The fire spread throughout the core to surrounding fuel channels, and the radioactivity in the chimney was increasing. A worker arriving for work noticed smoke coming out of the chimney. The chimney was only designed for the expulsion of the cooling fan’s air after it went through the core. The chimney was never meant to expel any smoke nor steam.

The operators did not know how to deal with the fire. First, they tried to blow the flames out by running the fans at maximum speed, but this just fed the flames even more. Secondly, the operators created a fire break by ejecting some undamaged fuel cartridges around the fire, and they also attempted to push some of the melted, damaged cartridges out of the reactor, but this proved impossible as the fuel rods stood in place, no matter how much force was applied.

Next, the operators tried to extinguish the fire using carbon dioxide. The new gas-cooled Calder Hall reactors which supplied electricity for the grid had just received a delivery of liquid carbon dioxide, which the operators hooked up to the charge face of the core, but it had absolutely no effect to the fire.

On 11 October, the blaze was at its worst. 11 long tons of uranium had caught fire, and the magnesium present in said cartridges was also now ablaze, with one thermocouple suggesting 3,100C (5600F), and the biological shield around the reactor was close to collapse. In a desperate attempt to bring the situation under control, the operators debated the use of water. This was risky, however, as the molten metal may oxidize with the water, leaving only hydrogen molecules, which could mix with air and explode, leading to severe damage to the containment structure. But with not much other options, they went ahead with the plan. The water, once again, was unsuccessful in extinguishing the fire.

At this point, reactor manager Tom Tuohy ordered every out of the reactor building except himself and the fire chief in order to shut off all cooling and ventilating air entering the reactor. The fire, in order to fuel itself, was desperately trying to pull air from every direction. “I have no doubt it was even sucking air in through the chimney at this point to try and maintain itself,” Tuohy remarked in an interview. He closed the inspection holes which was stuck open. The fire finally started to die down.

For the next 24 hours, water kept pumping throughout the pile until it was completely cold. The reactor tank itself has fortunately remained sealed since the accident and still contains around 15 long tons of uranium fuel. The pile is not scheduled for final decommissioning until 2037.

Aftermath

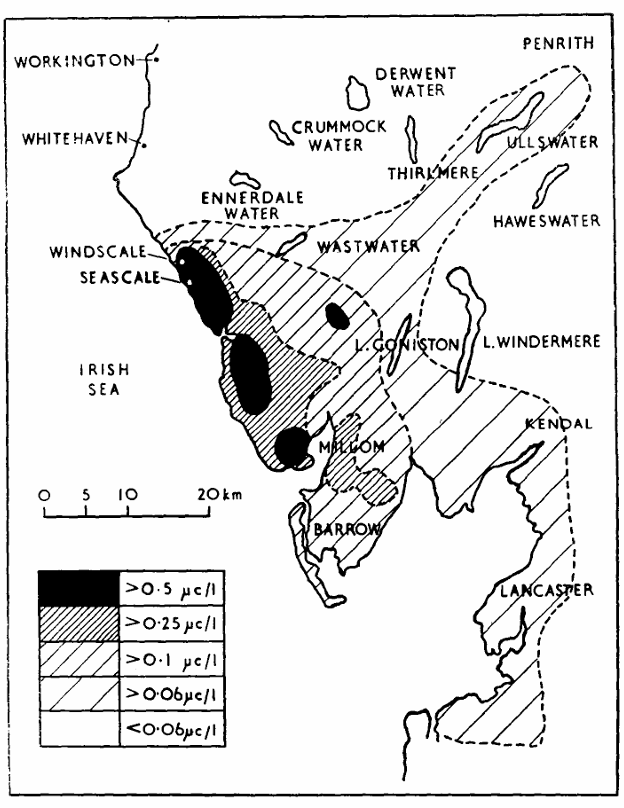

There was a release of radioactive material into the atmosphere that spread across the UK and Europe. The accident released around 20,000 curies of iodine-131, 594 curies of caesium-137, and 324,000 curies of xenon-133, along with other radioactive materials. The accident was largely kept a secret to the public, and it was later realized that the highly dangerous polonium-210 was also released during the fire.

In the following days, the British government tested samples on local milk, and it was found to be highly contaminated with iodine-131. Ingesting iodine-131 can give an increased chance of cancer of the thyroid, especially in children as their thyroids have not fully developed yet. As a result, restrictions were put in place. Milk from about 500 km2 of nearby countryside was destroyed (diluted a thousandfold and dumped in the Irish Sea) for about a month. However, no one was evacuated from the surrounding area.

The release of radiation by the Windscale fire is far greater than what was released during the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, but the fire was the worst reactor accident until Three Mile Island in 1979. The Windscale fire was retrospectively graded as level 5, an accident with wider consequences, on the International Nuclear Event Scale.

^ Map of the Windscale area showing contours of radioiodine contamination in

milk on the 13th of October 1957.

Leave a comment